The Loch Ness Project

Loch Ness

Centre

Nessie Dead or Alive |

Back

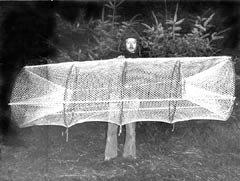

to Reflections |

It was recently announced that Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) was forming a Loch Ness Environment Panel........with a view to developing a code of practice for visiting monster hunters who might inadvertently cause damage to the loch's habitats, or individual creatures within it. This move was prompted by the proposal of a Swedish monster hunter and ufologist Jan Sundberg, to place a 6m long creel trap in Loch Ness. The SNH area manager Jonathan Stacey, made it clear that they had no policy on Nessie as such and the prime aim was to "protect the known from those pursuing the unknown". This is but the latest episode in a long interaction between those with responsibility for the loch and some of the unconventional activities which take place there. Scaffolding Cage 1933 Photograph *SMG Newspapers Ltd Reproduction without permission is forbidden without advance permission. To obtain permission please contact rights@smg.plc.uk  L.N.I.Large Eel Trap Early 1970's Copyright D. Raynor The Great Trap The next attempt was rather less sensational and came at the end of a decade of work by the Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau (LNI). Organised surface watches had failed to reveal the monster of popular expectation yet a huge volume of unexplained eyewitness testimony remained. Effort had moved underwater and thoughts were turning back to some of the original local "huge eel" ideas. In 1970, a study of the eel population was being made anyway, as one of the first attempts to incorporate some general biological research into the LNI activities. In addition to the eel traps, four "Great Traps" were made in case a small specimen of the larger quarry could be persuaded to enter. The traps were conical with the apex anchored to the bottom and measured 6ft high by 5ft across, with a spring loaded cover triggered by tension on a bait pouch inside.

Bob Love'sProposed Trap Nothing

was caught but this did not deter The LNI

Scientific Director, the American, Roy Mackal

or the leader of underwater activities, Bob

Love. They proposed a number of traps 18ft

by 6ft by 6ft built of plastic tube, which

could be purged with compressed air to bring

them to the surface if successful (Mackal, 1976 p 382). The

traps would be anchored to the loch bed with

a service platform moored at the surface.

A radio alarm would be given if the trap doors

were triggered. This temporary isolation of

a specimen (for tissue sampling and photography)

was seen as the final objective but the LNI

left the field in 1972 with no funding forthcoming.

It was to be 1984, before Bob Love's idea was

tried by a Liverpool civil servant named Steve

Whittle who obtained support from the Vladivar

Vodka company.

His plans called for a huge trap to be winched

into the loch by a Chinook helicopter and

maintained for a month at a depth of 30ms.

His proposal to use live fish as bait raised

concerns with the Fishery Board. This was

because of the risks of introducing disease

and because escaping fish, brought from elsewhere,

might breed with the native stock, so affecting

the gene pool. This was the point at which

the Loch Ness Project became involved since

they were working with the board at the time,

on a number of fish studies.

Mr. Whittles scheme

was approved with the proviso that the Project

agreed to undertake design, construction and

deployment of the trap. This was perhaps the

first move towards the Environment Panel of

the year 2000.

Thus by a strange

irony, the Project, in return admittedly,

for what amounted to two years funding, found

itself with a not inconsiderable technical

challenge with an objective it found difficult

to take seriously.

Things

had moved on by then and even the most optimistic

expectations for the size of an unknown animal

would be nowhere near the specified 60ft.

length of the trap. But a lot had to be taken

seriously. To begin with, the Project might

be wrong and a great deal of the Project's

work has always revolved around this notion!

The trap would have to be built ashore and

be photographed, fly over Fort Augustus beneath

a small helicopter without breaking up and

be photographed, land on the water and be

photographed, and be immersed 30ms down for

a month. As if that weren't enough, it must

pose no threat to navigation or the loch's

known inhabitants and in the event of a successful

capture, should any harm come to the captive,

then it would be too late to say that the

eventuality had not been taken seriously.

In any case, there was the matter of professional pride!

Therefore, in a

field at Fort Augustus, a true monster emerged

in the shape of a great cylinder or "creel".

It measured 60ft long and 20ft in diameter

with doors at either end. It was made from

"pultruded" fibreglass tube, reinforced with

larger plastic tubes, designed to be very

slightly buoyant in the water and of course,

light in air. The triangular gaps between

the tubes were over a metre on the longest

side; quite sufficient to allow native fish

and otters to pass through. This was a year

before it was definitely established that

seals enter the loch. The tubes were secured

by ties and tape. In the event of a really

huge capture the degree of success could probably

be measured by the amount of damage to the

trap!

The Vladivar Trap 1984 "Lift Off"

The

above examples, may help to show just how

easy it is to cause damage, however inadvertently

and just how much thought should go into avoiding

it. Even the quest for dead monsters has its

dangers. The LNI did some dredging and trawling

in 1969 and the early 70's.

In 1978, Adrian

Shine of the Loch Ness Project said " If there

have been large live animals in Loch Ness

for the past six thousand years, then there

are large dead animals there now." The Project

had been searching for skeletal remains at

Loch Morar, using everything from glass bottomed

boats and divers to dredging trials up to

1000ft down.

However, in the

course of the Project's scientific work, an

unexpected community of invertebrate animals

had been found there, including some interesting

Ice Age relicts (Shine

& Martin 1988). Dredging was therefore

shelved and that was just as well, since the

Project's coring programme was showing how

valuable the undisturbed sediment was in its

own right, particularly in Loch Ness. Here,

the depth ensures that water currents are

slow, preventing re-suspension of the material.

The loch's faultline origins give it a remarkable

"trench like" profile with a very flat bed,

which prevents the mud from slumping.

All this adds up

to a particularly well stratified historical

record of national importance (Bennett

& Shine, 1993). Some of the work,

such as the ROSETTA Project, is concerned with cores up to 6m long

which contain a wealth of information on the

last 10,000 years but some of the most important

indications of human impact lie within the first few centimetres (Jones

et al. 1997).

When another "hunt

for Nessie's bones" proposed dredging in the

mid nineties, the Loch Ness Project made representations

to Scottish Natural Heritage regarding the

protection of the special stratigraphic resource

on the loch's deep basin floors. This issue

together with those introduced above, is to

be addressed by the proposed code of practice.

In

the meantime, it will help those proposing

to work on Loch Ness to bear in mind the following:

1. British Waterways have a right of unobstructed navigation throughout the length of Loch

Ness since it forms a part of the Caledonian

Canal.

2. Activities which

might result in the pollution of the loch

are the remit of SEPA (Scottish Environmental

Protection Agency)

3. The Ness District

Salmon Fishery Board is a statutory body

protecting angling interests and aquatic habitats.

The Board would be concerned with matters

which might be damaging to the native fish

population, particularly the migratory salmon

and sea-trout. The netting of fish in Loch

Ness is prohibited, as is the introduction

of alien fish, as bait for example. Even native

species, may harbour disease. Escaping fish

of farmed origin can also have adverse genetic

effects when breeding with the native fish.

The Clerk, Ness

District Salmon Fishery Board, York House,

20 Church St.,

4. The SSPCA (Scottish Society for the Prevention of

Cruelty to Animals) would have concerns

over the risks and treatment of individual

animals. Traps, for example could pose a risk

for air breathing mammals such as seals and otters.

Scottish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SSPCA), Braehead

Mains .603 Queensferry Road ,Edinburgh .EH4

6EA

5. SNH (Scottish

Natural Heritage) are responsible for the general protection of habitats within the environment

and would be concerned if there was a possibility

of introducing alien species, for example

as eggs or spores, on equipment which had

been previously used in waters elsewhere.

They, along with the Loch Ness Project, have also expressed concern for the preservation

of the deepwater sediments.

The Loch Ness & Morar Project have records of most previous activities at Loch Ness and are engaged

in a number of current programmes. We may

be able to assist with information, advice

or refer enquiries to others.

Copyright this page : The Loch Ness Project

|

|