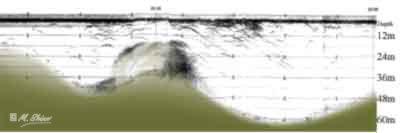

The Thermocline and Underwater Waves

The waters of the loch are seldom at rest. One of the earliest scientific

distinctions earned by Loch Ness was in 1904 when it was the site of the discovery

of large scale water movements known as internal seiches. The loch's profile has

an unusual trench-like regularity and is orientated North East and South West

in line with the prevailing winds. The warm overlying water of the epilimnion

is therefore easily transported down wind. The water then returns beneath the

surface like a conveyer belt. At the same time, in a typical South West wind,

the warm water is piled up at the North East end, tilting the thermocline down

in that direction. As the wind begins to drop, the warm water begins to flow back,

even against the wind, and gathering momentum overshoots the level and see-saws

with a steady 54 hour oscillation for up to a couple of weeks. This internal seiche

hardly affects the surface but the movement of millions of tons of water generates

huge underwater waves on the thermocline over 40m high and travelling at a majestic

1km per hour. The turbulence of these internal waves is the main process of mixing

heat downwards through the thermocline. They are at their height during the autumn

when the loch ceases to gain heat and equinoctial gales keep the cooling epilimnion

mixed to a uniform temperature. The difference in temperature between the epilimnion

and the water beneath becomes less as the thermocline settles deeper but it will

be Spring before the whole loch is mixed to a uniform 5.5o C.

This page copyright Shine, LNP

Close

Window